Tanzania is undergoing one of the most ambitious expansions of its health workforce in decades, a national effort that aims to professionalise community health and bring essential care closer to millions of households. By 2028, the country plans to train and deploy nearly 140,000 community health workers (CHWs) across its 4,263 mitaa and more than 64,000 hamlets, creating what leaders describe as a “frontline army” against disease outbreaks and long-standing public health challenges.

For young workers like Chiku Abdallah, the transformation is deeply personal. The 20-year-old CHW from Mtundilikile village in Lindi region remembers when she could only share basic health advice that she herself barely understood.

“I had no formal training,” she recalls. “I warned people about disease outbreaks, but I didn’t fully understand what that meant or how to protect myself.”

Today, her work is very different. Armed with a digital tablet, essential medical devices and a structured reporting system, Abdallah says she now feels like a true professional.

“I know how to protect myself, how to educate the community, and how to identify risks early,” she says , a shift that reflects the nationwide effort to turn community health volunteers into skilled, frontline workers.

A Training Programme Born Out of Crisis

The 2025 Marburg virus outbreak in Kagera region proved to be a turning point, revealing both the strengths and the vulnerabilities of Tanzania’s community-based health system.

Dr Norman Jonas, the National Coordinator for Community-Based Health Services, notes that the first alerts of the outbreak came from community health workers.

“But these workers were operating with limited tools and no unified reporting structure,” he says. “We realized their potential , but also their limitations.”

The outbreak demonstrated that early detection cannot depend on chance. Many CHWs lacked proper training, struggled to communicate effectively, and lacked professional recognition , all factors that hindered rapid response.

Local leaders noticed these gaps too.

“We faced challenges with untrained CHWs,” says Kitenge Seleman, Ward Executive of Kitengule.

“They lacked the professionalism needed to convey accurate health information. Training was essential.”

Building a Skilled Frontline Workforce

In 2024, Tanzania launched the Integrated and Coordinated Community Health Workers Programme, a structured initiative designed to standardize training and elevate CHWs to a recognized health cadre.

The first cohort 3,600 CHWs graduated in August 2025 after a rigorous six-month training programme, split equally between classroom learning and supervised field practice. Only individuals with a minimum secondary education were eligible.

For CHWs like Bamvua Ashim Mkundia from Luchemi village, the difference is life-changing.

“Before training, I didn’t know how to identify illnesses,” he says.

“Now I can check blood pressure, temperature, weight, and recognize early signs of infectious and non-communicable diseases.”

This early detection can be life-saving, especially in remote areas where dispensaries are far from homes and small illnesses often escalate into severe complications before people seek care.

Abdallah says she now visits around 15 households per day, delivering detailed health education, tracking immunisation rates, and monitoring vulnerable children and mothers. “This job cannot be rushed,” she says. “Our communities depend on us.”

Digital Tools for a Modern Health System

One of the programme’s major innovations is the rollout of tablets equipped with the Unified Community System (UCS), a single digital platform designed to solve the long-standing problem of fragmented health data.

“Before this system, every stakeholder used their own reporting tools,” explains Zawadi Dakika, Program Manager at the Benjamin Mkapa Foundation (BMF).

“Now the entire community health system speaks one language.”

The tablets allow CHWs to input patient data, track high-risk cases, and send alerts instantly to nearby facilities. If a CHW encounters a dangerous symptom, like extremely high fever or concerning bleeding the system automatically issues an urgent referral notification.

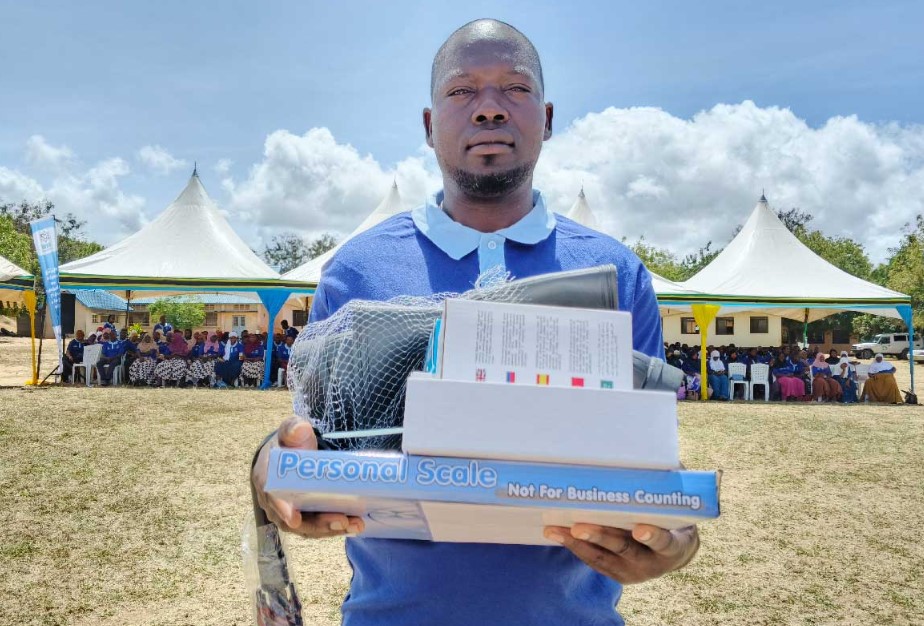

Alongside tablets, CHWs receive essential equipment such as blood pressure monitors, glucose testing kits, thermometers, nutrition indicators, boots, umbrellas, and medical bags, practical tools that enhance their mobility and effectiveness in rural environments.

A New Backbone for Tanzania’s Health System

The government sees this new force not only as a public health solution, but as a strategic investment in national resilience.

Chief Medical Officer Dr Grace Magembe emphasised this at the first graduation ceremony.

“They may not wear uniforms or combat gear,” she said, “but they are an army we depend on heavily.”

By shifting routine community-level work to trained CHWs, health facilities can remain fully staffed instead of sending nurses on time-consuming outreach trips. The system strengthens disease surveillance, improves outbreak preparedness, and speeds up identification of both infectious diseases like Marburg and chronic illnesses like hypertension.

With a structured career path, standardized training, and steady support from the Ministry of Health and implementing partners, Tanzania hopes this army of community health workers will permanently strengthen the connection between facilities and the communities they serve.

If successful, the initiative could become a model for other African nations seeking to modernize health delivery at the last mile, proving that the strongest healthcare systems are often built from the ground up.