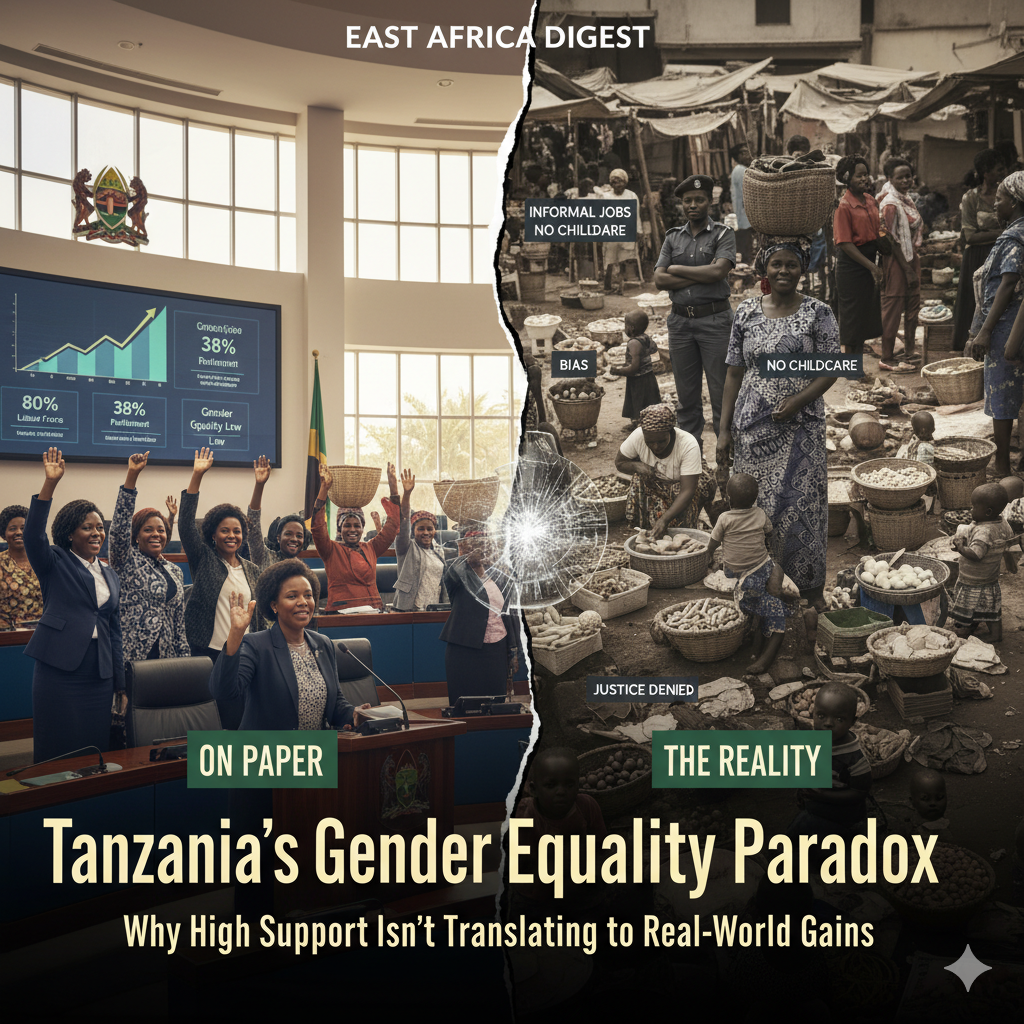

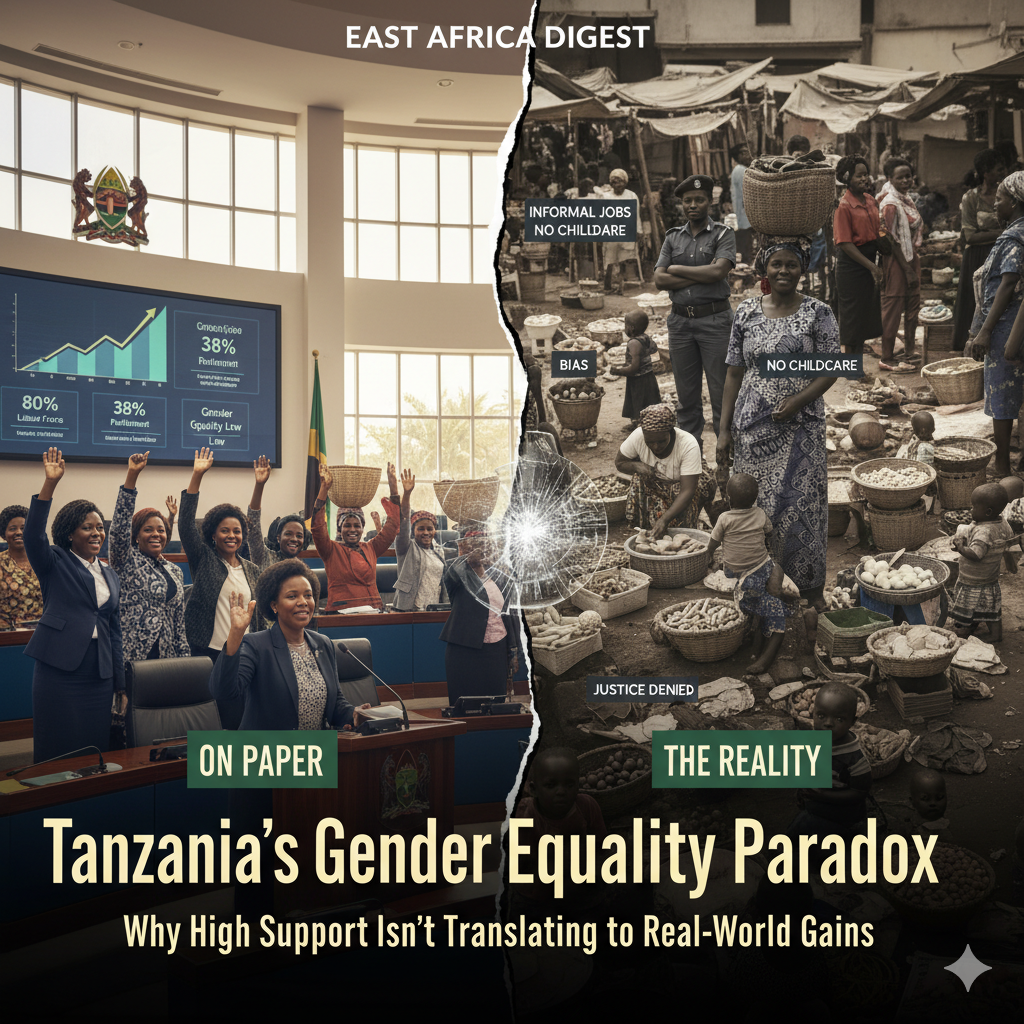

Tanzania is posting numbers that should make it a leader in gender equality. Women’s labour-force participation has soared to 80%, far outpacing the sub-Saharan African average. In politics, women hold a formidable 38% of seats in the National Assembly. Legally, the nation has ratified every major international and regional treaty on women’s rights, from CEDAW to the Maputo Protocol.

The public is on board, too. A new Afrobarometer survey confirms that a strong majority of Tanzanians support gender equality.

But an East Africa Digest analysis of this new data, paired with national labour statistics, reveals a deep and troubling disconnect. Despite progressive laws and popular support, Tanzanian women remain systematically locked out of economic security and face institutional blind spots that fail to protect them.

This is Tanzania’s equality paradox: a country that champions women on paper but sidelines them in practice.

The “On Paper” Success Story

On the surface, Tanzania’s commitment is impressive. The surge in female labour participation from 67% in 2000 to 80% in 2019 (World Bank, 2022) is a massive economic shift. The political quota system has successfully embedded women in the legislature (IPU, 2024).

These gains aren’t accidental. They are the result of deliberate policy, including the National Strategy for Gender Development, aimed at boosting girls’ education and women’s access to finance. The legal framework, anchored by the Constitution, provides a solid foundation for equality.

But this foundation is proving unable to support the weight of reality.

The Reality: Locked in the Informal Economy

The 80% labour figure, while high, masks a critical vulnerability. The 2020/2021 Integrated Labour Force Survey reveals a harsh truth: informal employment is rising (from 22% in 2014 to 29% in 2020/2021), and women are more likely than men to be in these jobs (National Bureau of Statistics, 2022).

This means that while women are working, they are disproportionately trapped in low-paid, insecure roles with no benefits, no formal contracts, and no path to advancement. They are, in effect, powering the economy from its most precarious rung.

The Investigation: What Tanzanians Really Think

The new Afrobarometer Round 10 survey provides the “why.”

When asked about hiring, the public overwhelmingly supports gender equality. Yet, they see exactly why women are underrepresented in the formal job sector. Respondents identified the primary barriers not as “lack of skill” or “ambition,” but as systemic failures:

- Inflexible work arrangements that make it impossible to balance work and family life.

- A critical lack of childcare options.

- A persistent employer preference for hiring men.

The public understands the problem is structural. Women aren’t failing to get good jobs; the system is failing to let them in.

A Crisis of Protection: The Glaring Contradiction

The most alarming finding from the investigation lies in public perception of safety and justice.

According to the Afrobarometer data, most Tanzanians do not see gender discrimination and sexual harassment as “common problems.”

This response seems to fly in the face of global and regional reports on gender-based violence. But a follow-up question reveals a stunning contradiction: an overwhelming majority of these same citizens say the police and courts must do more to protect women and girls from these exact threats.

This paradox is the crux of the issue.

It suggests that discrimination and harassment may be so normalized that they aren’t registered as “common problems” but rather as a fact of life. Yet, citizens intrinsically know that the institutions designed to protect them—the police and the judiciary—are failing.

The public may not use the language of “systemic harassment,” but their demand for more protection is a clear vote of no confidence in the state’s ability to keep women safe.

Conclusion: Beyond Paper Policies

Tanzania’s challenge is no longer one of law or public opinion. Its laws are clear, and its people are supportive.

The gap is one of implementation and institutional will.

The data shows that progress has stalled because the structural barriers—employer bias, the childcare deficit, and a justice system that citizens deem inadequate—have not been dismantled.

Until Tanzania moves from de jure (legal) equality to de facto (real-world) equality, the impressive statistics on female participation will only serve to mask the deep-seated inequalities that define the daily lives of millions.